PC: To continue on Duchamp for a bit. Was he a good chess teacher?

JC: I was using chess as a pretext to be with him. I didn't learn, unfortunately, while he was alive to play well. I play better now, although I still don't play very well. But I play well enough now that he would be pleased, if he knew that I was playing better. So that when he would instruct me in chess, rather than thinking about it in terms of chess, I thought about it in terms of Oriental thought. Also he said, for instance, "don't just play your side of the game; play both sides." That's a brilliant remark and something people spend their lives trying to learn. Not in chess, but in anything.

PC: Right. Oh absolutely. You've been interested in Oriental thought for twenty-some years now. Has it always worked for you in the sense of providing systems and structures? What was the initial appeal?

JC: I got involved in Oriental thought out of necessity. I was very disconcerted both personally and as an artist in the middle forties. I saw no reason for writing music in a society as it was then and with the arts as they were. I saw that all the composers were writing in different ways, that almost no one among them, nor among the listeners, could understand what I was doing, in the way that I understood it. So that anything like communication as a raison d’être for art was not possible. I determined to find other reasons, and I found those reasons because of my personal problems at the time, which brought about the divorce from Xenia. I considered psychoanalysis, but I didn't engage in it because a particular psychologist said he'd fix me so that I could write more music, and I was already writing too much. So through circumstances, I substituted the study of Oriental thought for psychoanalysis. In other words, it was something that didn't amuse me, to grope with my -- myself. But it was something I absolutely needed.

PC: It is fascinating that you picked that. I mean there could have been various other ways or ideas.

JC: There aren't too many. What would you suggest?

PC: Well, I don't know what kind of problems there were at that point.

JC: Well, if you had a disturbance both about your work and about your daily life, what are you going to do?

PC: Well, you try a lot of things, I suppose. Right?

JC: None of the doctors can help you, our society can't help you; our education doesn't help us. It's singularly lacking in any such instruction. Furthermore, our religion doesn't help us. The Methodist Church that I was raised in spent its whole time raising money for the Foreign Missionary Society.

PC: You should have become a foreign missionary.

JC: There isn't much help for someone who is in trouble in our society. I had eliminated psychiatry as a possibility. You have Oriental thought, you have mythology. I already knew Joseph Campbell [scholar, 1904-1987] very well. The closeness of mythology to Oriental thought made me think of Oriental Philosophy as a possibility. Another possibility is astrology, curiously enough. It can be useful in such cases. Or occult thought, or the thinking, for instance, of Rudolf Steiner. But by the time you get into actual philosophy, you're practically in Oriental philosophy. So that's why I did it. It was a book of [Aldous] Huxley's [writer, 1894-1963] that lead me to make this conclusion. It was a book called The Perennial Philosophy. In that book I saw that all thought of that nature was the same, whether it came from Europe or Asia. I found that the flavor of Zen Buddhism appealed to me more than any other. It was tastier. And at that very time D.T. Suzuki [writer, 1870-1966] came here so I was with him for three years [1949-51].

PC: That was the end of the forties?

JC: Yes, then my next thought was, when I got to know him a bit, was if he would okay my music, then I would be hunky-dory. So I asked him one day, "What have you to say about music?" And he said, "I know nothing about music." I subsequently saw an interesting book that he wrote on the arts. But what he was saying in his teachings was I will not give you any diploma. Which is the correct Zen teaching?

PC: Keep on --

JC: Yes.

PC: That's what's wrong with diplomas I think. People think that you stop. They should give out keys or something, rather than wall hangings.

JC: Then when I met through Joseph Campbell and Jean Erdman, I met Alan Watts [philosopher, 1915-1973]. I criticized to him his frequent reference -- when in his books, he thought music would explain what he was about, just like Beethoven. I explained to him that Beethoven was not doing what Zen was talking about, and that we were just beginning in our work to do that. So he came to a concert of mine and disliked it very much. He said there was no reason for him to go to such a concert listening to the sounds, you know. Christian Will said to him "Yes, but the sounds are somewhat different in a concert hall." Anyway, Watts then wrote in a text called, I forget, Square Zen and Beat Zen ["Beat Zen, Square Zen, and Zen"], or something.

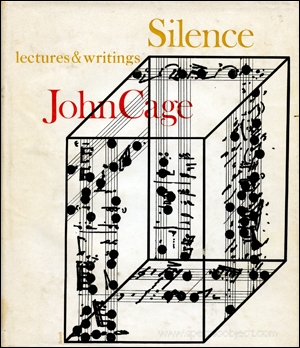

He wrote that I had misinterpreted Zen Buddhism. That caused me to, in the preface to Silence, to defend Zen against me, by saying that I would not have done what I was doing except for Zen, but that I didn't want Zen blamed for what I was doing. When I sent a copy of Silence to Alan Watts, his whole view had changed and he then… In other words, he was a man who had no understanding of the arts. He had a good understanding of the language, and books and you could tell that by visiting him in his home and by the pictures he had on the wall, which were 1890ish.

PC: Oh really.

JC: So anyway once I wrote Silence, he was in accord with my work and frequently came to my concerts.

PC: I've always been fascinated by the writings that you do and the lectures and all of the enormous amount of activity. Yet, it's done so gently it seems.

JC: I try to do, in the different things, what I can.

PC: Are they separate in a way or do you think they are all --

JC: No, they are distinctly coming together. The writing is behind the music. I don't mean to say subordinate, but lagging right behind.

PC: How much have the books affected your activities? There are now what, four, five? How have they affected things for you?

JC: They made life miserable.

JC: Thoreau said that the -- Thoreau is the last one for me known to be since Duchamp, and I discovered that Thoreau was an artist. Did you know that?

PC: Yes.

JC: You did?

PC: A little bit.

JC: Has anyone remarked on the beauty of his art? I think I'm the first one to notice it because if I'm not, I want to know. I'm going to write Walter Harding [1917-1996] who is the secretary of the Thoreau Society. He knows better than anyone else. Anyway I have this lecture now called "Empty Words" which is not syntactical, and which uses projection of Thoreau's slides. I have some 600 of them made and they are astonishing in reference to Modern Art and also to Oriental Art.

PC: When did you start Thoreau?

JC: In '67.

PC: How did that appear?

JC: Well, actually, that's been recounted in a bulletin of the Society.

PC: Oh.

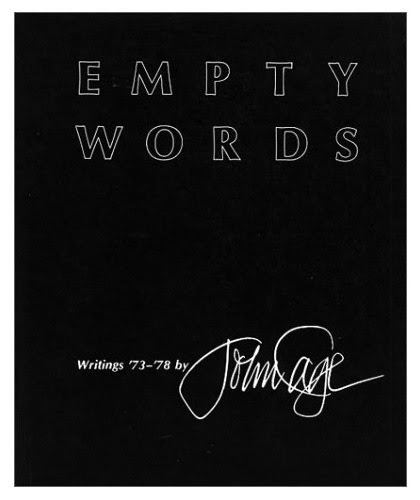

JC: I tell the story and I could show you the "Empty Words" but they were just taken away for publication.

PC: That's a marvelous line.

JC: But the drawings are amazing in relation to early Mondrian and this --

PC: One thing is, did you ever do the Jasper Johns before he adapted the Duchamp thing? Is that the only one?

JC: You mean the --

PC: From the Dwan [sic] --

JC: Oh, you mean from Merce's work?

PC: Right.

JC: No.

JC: Yes, he did some costumes for many of the dancers and dyed them himself. He did, second-hand; he frequently dyed them when other artists had done the work but would not themselves make the costumes. He frequently made them. He did the set and costumes with the help of Mark Lancaster [set designer, 1938] before the French Opera last November, and now he's done a great deal for Merce. The sets ascribed to Rauschenberg, Minuga and Summer Space, both of those were done by both of them.

PC: Oh really. That's interesting.

JC: The ideas were probably Bob's, but Jap [Jasper Johns] helped with the work.

PC: You had in 1958, at Stable Gallery, an exhibition of scores.

JC: That was arranged both by Bob and Jap.

PC: It was? You haven't done that since, have you?

JC: Yes, Carl Solway Gallery, in Cincinnati.

PC: Oh, in Cincinnati.

JC: They use my manuscript and make shows that occur; every now and then, when I go to some university, there is a whole show of it. The plexigrams for Marcel, and the lithographs, and then the Mushroom Book with Lois Long [writer, 1918-1974] and --

PC: How did the plexigrams come about?

JC: They were commissioned by a lady in Cincinnati, Alice Weston, who has a certain interest in both music and painting. She has commissioned Gunther Schuller [composer, 1925] to do work, a symphony, and it was through her and her husband that I was made composer in residence at the University of Cincinnati. Then she got the idea that though I had not done any lithographs, I could do some. She asked me to do some. Marcel had just died and I had been asked by one of the magazines here to do something for Marcel. I had just before that heard Jap say, "I don't want to say anything about Marcel," because they had asked him to say something about Marcel in the magazine too.

JC: I was using chess as a pretext to be with him. I didn't learn, unfortunately, while he was alive to play well. I play better now, although I still don't play very well. But I play well enough now that he would be pleased, if he knew that I was playing better. So that when he would instruct me in chess, rather than thinking about it in terms of chess, I thought about it in terms of Oriental thought. Also he said, for instance, "don't just play your side of the game; play both sides." That's a brilliant remark and something people spend their lives trying to learn. Not in chess, but in anything.

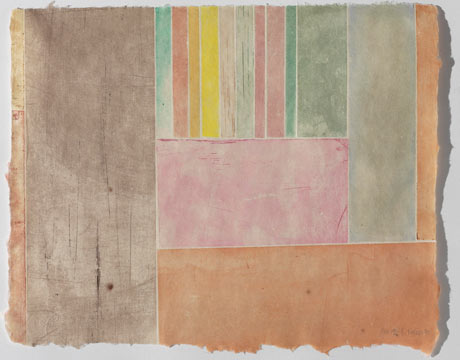

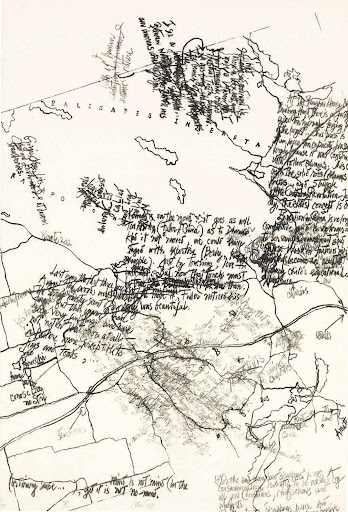

John Cage's HV2, No 17b.

PC: Right. Oh absolutely. You've been interested in Oriental thought for twenty-some years now. Has it always worked for you in the sense of providing systems and structures? What was the initial appeal?

JC: I got involved in Oriental thought out of necessity. I was very disconcerted both personally and as an artist in the middle forties. I saw no reason for writing music in a society as it was then and with the arts as they were. I saw that all the composers were writing in different ways, that almost no one among them, nor among the listeners, could understand what I was doing, in the way that I understood it. So that anything like communication as a raison d’être for art was not possible. I determined to find other reasons, and I found those reasons because of my personal problems at the time, which brought about the divorce from Xenia. I considered psychoanalysis, but I didn't engage in it because a particular psychologist said he'd fix me so that I could write more music, and I was already writing too much. So through circumstances, I substituted the study of Oriental thought for psychoanalysis. In other words, it was something that didn't amuse me, to grope with my -- myself. But it was something I absolutely needed.

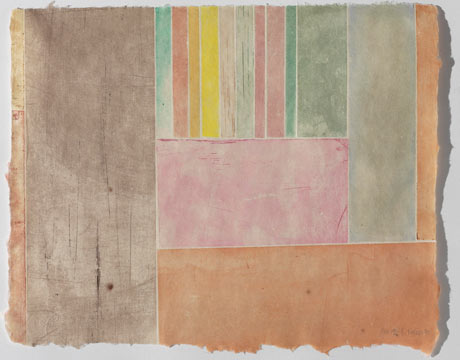

John Cage, Haiku, 1952

PC: It is fascinating that you picked that. I mean there could have been various other ways or ideas.

JC: There aren't too many. What would you suggest?

PC: Well, I don't know what kind of problems there were at that point.

JC: Well, if you had a disturbance both about your work and about your daily life, what are you going to do?

Score Without Parts (40 Drawings by Thoreau): Twelve Haiku, 1978

PC: Well, you try a lot of things, I suppose. Right?

JC: None of the doctors can help you, our society can't help you; our education doesn't help us. It's singularly lacking in any such instruction. Furthermore, our religion doesn't help us. The Methodist Church that I was raised in spent its whole time raising money for the Foreign Missionary Society.

PC: You should have become a foreign missionary.

John Cage · Haiku Envelope. 1952, Print, 7.5 x 14 inches

JC: There isn't much help for someone who is in trouble in our society. I had eliminated psychiatry as a possibility. You have Oriental thought, you have mythology. I already knew Joseph Campbell [scholar, 1904-1987] very well. The closeness of mythology to Oriental thought made me think of Oriental Philosophy as a possibility. Another possibility is astrology, curiously enough. It can be useful in such cases. Or occult thought, or the thinking, for instance, of Rudolf Steiner. But by the time you get into actual philosophy, you're practically in Oriental philosophy. So that's why I did it. It was a book of [Aldous] Huxley's [writer, 1894-1963] that lead me to make this conclusion. It was a book called The Perennial Philosophy. In that book I saw that all thought of that nature was the same, whether it came from Europe or Asia. I found that the flavor of Zen Buddhism appealed to me more than any other. It was tastier. And at that very time D.T. Suzuki [writer, 1870-1966] came here so I was with him for three years [1949-51].

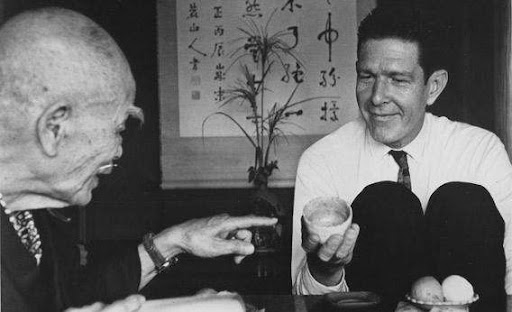

John Cage meets D.T. Suzuki in 1962.

PC: That was the end of the forties?

JC: Yes, then my next thought was, when I got to know him a bit, was if he would okay my music, then I would be hunky-dory. So I asked him one day, "What have you to say about music?" And he said, "I know nothing about music." I subsequently saw an interesting book that he wrote on the arts. But what he was saying in his teachings was I will not give you any diploma. Which is the correct Zen teaching?

PC: Keep on --

JC: Yes.

John Cage meets D.T. Suzuki in 1962.

PC: That's what's wrong with diplomas I think. People think that you stop. They should give out keys or something, rather than wall hangings.

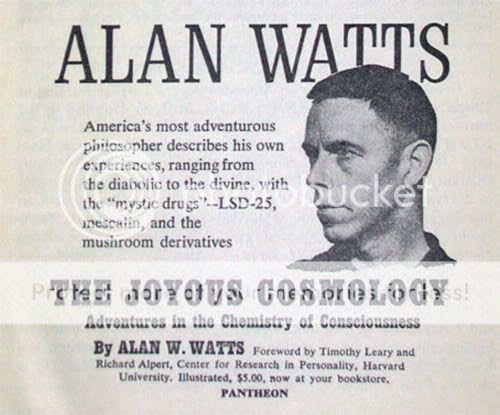

JC: Then when I met through Joseph Campbell and Jean Erdman, I met Alan Watts [philosopher, 1915-1973]. I criticized to him his frequent reference -- when in his books, he thought music would explain what he was about, just like Beethoven. I explained to him that Beethoven was not doing what Zen was talking about, and that we were just beginning in our work to do that. So he came to a concert of mine and disliked it very much. He said there was no reason for him to go to such a concert listening to the sounds, you know. Christian Will said to him "Yes, but the sounds are somewhat different in a concert hall." Anyway, Watts then wrote in a text called, I forget, Square Zen and Beat Zen ["Beat Zen, Square Zen, and Zen"], or something.

He wrote that I had misinterpreted Zen Buddhism. That caused me to, in the preface to Silence, to defend Zen against me, by saying that I would not have done what I was doing except for Zen, but that I didn't want Zen blamed for what I was doing. When I sent a copy of Silence to Alan Watts, his whole view had changed and he then… In other words, he was a man who had no understanding of the arts. He had a good understanding of the language, and books and you could tell that by visiting him in his home and by the pictures he had on the wall, which were 1890ish.

Alan Watts, the "Beat" Zen. Photo by Nat Farbman

PC: Oh really.

JC: So anyway once I wrote Silence, he was in accord with my work and frequently came to my concerts.

PC: I've always been fascinated by the writings that you do and the lectures and all of the enormous amount of activity. Yet, it's done so gently it seems.

JC: I try to do, in the different things, what I can.

PC: Are they separate in a way or do you think they are all --

The original version of John Cage's “4'33” (In Proportional Notation)

JC: No, they are distinctly coming together. The writing is behind the music. I don't mean to say subordinate, but lagging right behind.

PC: How much have the books affected your activities? There are now what, four, five? How have they affected things for you?

JC: They made life miserable.

John Cage. 17 Drawings by Thoreau. Print

PC: The telephone keeps ringing, people come with tape machines.JC: Thoreau said that the -- Thoreau is the last one for me known to be since Duchamp, and I discovered that Thoreau was an artist. Did you know that?

PC: Yes.

JC: You did?

PC: A little bit.

JC: Has anyone remarked on the beauty of his art? I think I'm the first one to notice it because if I'm not, I want to know. I'm going to write Walter Harding [1917-1996] who is the secretary of the Thoreau Society. He knows better than anyone else. Anyway I have this lecture now called "Empty Words" which is not syntactical, and which uses projection of Thoreau's slides. I have some 600 of them made and they are astonishing in reference to Modern Art and also to Oriental Art.

PC: When did you start Thoreau?

JC: In '67.

PC: How did that appear?

John Cage, Presentation in Out Off for the concert Empty Words, Teatro Lirico, 1, 12, 1977

JC: Well, actually, that's been recounted in a bulletin of the Society.

PC: Oh.

JC: I tell the story and I could show you the "Empty Words" but they were just taken away for publication.

PC: That's a marvelous line.

JC: But the drawings are amazing in relation to early Mondrian and this --

PC: One thing is, did you ever do the Jasper Johns before he adapted the Duchamp thing? Is that the only one?

JC: You mean the --

PC: From the Dwan [sic] --

"Rainforest" Merce Cunningham and Meg Harper,

decor: Andy Warhol ,"Silver Clouds" costumes: Jasper Johns, Paris, 1970

JC: Oh, you mean from Merce's work?

PC: Right.

JC: No.

Choreography: Merce Cunningham. Music: David Tudor. Design: Mark Lancaster.

PC: He had done some other ones?JC: Yes, he did some costumes for many of the dancers and dyed them himself. He did, second-hand; he frequently dyed them when other artists had done the work but would not themselves make the costumes. He frequently made them. He did the set and costumes with the help of Mark Lancaster [set designer, 1938] before the French Opera last November, and now he's done a great deal for Merce. The sets ascribed to Rauschenberg, Minuga and Summer Space, both of those were done by both of them.

John Cage, Solo for Voice, n. 11

PC: Oh really. That's interesting.

JC: The ideas were probably Bob's, but Jap [Jasper Johns] helped with the work.

PC: You had in 1958, at Stable Gallery, an exhibition of scores.

Robert Rauschenberg seated on Untitled (Elemental Sculpture) with White Painting (seven panel) behind him at the basement of Stable Gallery, New York 1953

JC: That was arranged both by Bob and Jap.

PC: It was? You haven't done that since, have you?

JC: Yes, Carl Solway Gallery, in Cincinnati.

Carl Solway Gallery Digging in the Archives: John Cage, Williams Mix

PC: Oh, in Cincinnati.

JC: They use my manuscript and make shows that occur; every now and then, when I go to some university, there is a whole show of it. The plexigrams for Marcel, and the lithographs, and then the Mushroom Book with Lois Long [writer, 1918-1974] and --

John Cage, Mushroom Book, Plate VIII, lithograph in handwriting, 1972, 22.5 x 15 inches

JC: They were commissioned by a lady in Cincinnati, Alice Weston, who has a certain interest in both music and painting. She has commissioned Gunther Schuller [composer, 1925] to do work, a symphony, and it was through her and her husband that I was made composer in residence at the University of Cincinnati. Then she got the idea that though I had not done any lithographs, I could do some. She asked me to do some. Marcel had just died and I had been asked by one of the magazines here to do something for Marcel. I had just before that heard Jap say, "I don't want to say anything about Marcel," because they had asked him to say something about Marcel in the magazine too.

Music of John Cage. Carl Solway Gallery

So I called them, the plexigrams and lithographs, I called them Not Wanting to Say Anything about Marcel, quoting Jap without saying so. But doing that isn't saying instead of saying something about him. To subject the dictionary to chance operations and to use the Eakin [sic] to introduce this dictionary to images and to make a transition from language to imagery and numbers, and then as I say in the preface to all that, I think Marcel would have enjoyed it. He, I found a remark of his after I had done the work, that he enjoyed looking at the signs that were weathered because where letters were missing and things, that it was fun to figure out what the words were before they got weathered. The reason, in my work, that they weathered is because, is about the fact that he died. So every word is in a state of disintegration.

Not Wanting to Say Anything About Marcel, 1969.

Silkscreens on Plexiglas in wooden bases and a lithograph.

PC: How did you like that business of actually putting it all together?

JC: Well, I don't do that work. It was done by Calvin Sumsion. I composed it.

PC: Oh I see, because I couldn't figure out which part --

JC: I wrote it, first we worked together. Then I was able to tell him to do something, and then he would send back the work completed. Albers has used such methods, hasn't he? With his work, or he gives it to some craftsman to do those things. Many artists now, when they don't know a particular craft, learn how to tell a craftsman what to do. It began with tapestry and relics.

PC: How did you like doing the lithographs and all that?

JC: Oh, it's very exciting and it made me understand why so many artists become alcoholics, because when you put a blank sheet of paper into the press and something actually happens to the paper when it comes out, it's so exciting that you just have to have a drink. Whereas music, you can't drink, because the occasion of hearing the music is a public one, not a private one and the drinking all takes place after the concert.

PC: So the rituals are different.

JC: And it's completely different. You learn as an artist why it's pleasant to drink alone, you see, rather than with other people. That is what leads to alcoholism.

John Cage, Mushroom Book, Plate X, lithograph in handwriting, 1972, 22.5 x 15 inches

PC: Because a lot of them have that disastrous problem. One thing that's always interested me and that's the kind of visual qualities of your scores.

JC: It all comes from [inaudible].

PC: But even before?

JC: Well, they're not that interesting before, I think.

PC: I'm kind of thinking of the earlier ones I have seen. I don't think I've seen ones that early.

JC: I didn't make them in order to be beautiful either. I made them in order to notate things that couldn't be notated any other way. With magnetic tape we became aware that sound was a field rather than just the scales, major and minor. So having the conventional note only permitted you to get to those particular points and we needed to go to any point. And graphic notation developed, and made many music manuscripts interesting visually. I received this in the mail, a young musician who I don't know, but you immediately see it's interesting visually.

Color lithograph by Lois Long in Mushroom Book, Plate VIII, 1972, 22.5 x 15 inches

PC: It's like Frank Stella [artist, 1936].JC: It's all music. It's very beautiful looking, don't you think? It's an impressive letter. I haven't read it all yet but you see it's quite marvelous, and would interest an artist. Who would send such a beautiful letter through the mail? That's one of the advantages of being well-known.

PC: Things come in the mail. I want to ask you one other thing about the books and then I want to talk about the New School classes, where there were so many people who were artists. One thing is the Richard Kostelanetz [artist and author, 1940] book which is only four years -- how old? Three years, four years, something like that.

JC: Richard said that it -- that the books were being returned to the press. Did you know that? That they are not selling.

PC: No, there are only about 200 left.

JC: Oh really?

PC: Yeah, they've all been sold.

JC: He said that it was not, that it was not selling.

PC: He's neurotic about it, I know.

John Cage in high school

JC: I think he's probably noticing a --

PC: But, no, they remained at, I think it was 200 copies because they have this new economic czar over there by a certain day, and it's erased, which is silly but --

JC: But, it's been reprinted in other countries, translated.

PC: Oh, yes, yeah. There's lots of interest in it, getting out there. Do you, have you been able to notice any response from people because of that? Have you gotten letters?

JC: Oh yeah.

PC: Commentaries, things like that?

JC: The text I wrote, "When I Was Twelve Years Old," about Latin American problems, that is in Richard's book, aroused a great deal of interest in South America. There were people who never liked my music before and now think it's just great.

PC: Oh really, fantastic.

JC: I had a translator in Germany, Peter Schnagle [sic], another composer, a very good composer, his wife translated the text, I guess, but he made the preface to the German edition.

John Cage, Eninka 22, 1986, burned, smoked and branded

Japanese Gampi paper mounted on paper (unique impression), 64.14 x 47.94 cm,

PC: That's terrific. You know one thing that’s very interesting since so many people have talked about it and written about it was the classes at --

JC: In the New School.

PC: In the New School where there were classes like Hansen. What was your plan, you know, when you --

John Cage, Lithograph B from Not Wanting to Say Anything About Marcel, 1969

JC: My plan was to -- the first meeting was to explain to the students what I was then doing. Then the next class was to find out from them what they were doing, in other words, the class was conceived as people meeting one another. From those two classes on, there was no further teaching; it was doing work. Whoever had done any work would simply show it. Then we would all comment on it. I warned them that the only thing I would do in the way of teaching was if they were being too conservative, that I would suggest that they be more experimental.

PC: Did you have to do that in any instance?

JC: In some cases. But not people whose names we would know. The one who could always be depended upon for having done some work was Jackson Mac Low [poet, 1922-2004] whose work then was little well-known. He used the class effectively for himself and effectively for us to perform his simultaneous poetry which he was just then beginning. Alan Kaplan also used the class to make events which were also being given in galleries about that time.

PC: And Mac Low used to give poetry readings too, didn't he? Once in awhile?

JC: It may be, but his work was not easy for him to get many people to read; whereas, in this class it was possible. One thing I insisted upon in the class, I said, "Don't bring any work to the class that you can't do. If you can't do it here, don't bring it here."

PC: So performance was important.

JC: Yes, it had to be. I had learned from my teacher Adolf Weiss, who had written a lot of music that was never performed, and he became a bitter old man. I determined then that the business of composing isn't finished until the work is performed. And that's something implicit in painting. You don't leave the painting unpainted.

PC: And hopefully it gets shown. Which is the next --

JC: Well, that is one of the troubles with painting is that you yourself can see it all alone and that's one of the great things about music is that it really needs not only to be heard by people, but it needs to be performed by people other than the composer.

PC: Were you happy with the results of that class? Do you think it worked as a teaching activity for the students and for yourself?

JC: I think that it was a happy occasion in the sense that Black Mountain College was a happy college. Yesterday, I was interviewed about Black Mountain and a very bright girl interviewing me said what interested her was how it was that all those people came together, how was it that all one hundred students were interesting, you know? Though I didn't have a hundred, it was more like eight to twelve, they were all interested. That made a lively situation.

PC: Well, I think one of the things that struck me at Black Mountain was that it was a place where people who wanted to be professional went, rather than somebody who wanted to get a degree to teach. I think that the university --

Merce Cunningham, Black Mountain College, 1953 Summer Art Institute

JC: That was the same case at the New School, there was no question of degrees. What was her name, the lady in charge of the school then? Meyer. What was her first name? It began with, Clara Meyer. She was an inspired educational leader and when she became weak in the New School, was when the New School started going downhill. By downhill I mean giving an honorary degree to that wretched, wretched Russian poet [inaudible].

PC: Well, you know, what can you do? Have you found that your associations with the artists have been useful to you in your own work, in terms of ideas or bouncing things off of them?

JC: They are in one way or another in dialogue.

David Tudor, Black Mountain College 1953 Summer Institute in the Arts

JC: I think dialogues is a better word than art, rather than things like people say, they say influence. I don't think they influence one another; I think they respond to one another.

PC: So that there is more of a dialogue rather than a putting on of something.

JC: Oh yes.

PC: Have there been ways that you noticeably comment or comment on, you know, aspects of the dialogue like that? Or do you just too confused?

JC: I wrote about it in the Kostelanetz book, The Arts and Dialogues, isn't it? What they believe now is that the last person to speak is music and the rest had better reply. Where is it? It's dated here, in '64. And I still believe it.

"The arts are not isolated from one another but engage in dialogue. Much of the new music composing means that are indeterminate, notations that are graphic is a reply to modern painting and sculpture. Marcel Duchamp's painting on glass, which is not separate from its environment, the found object, the drops strings. However, each art can do what another cannot. It is predictable that the new music will be answered by a new painting, one which we have not yet seen."

I was recently at Cranbrook School near Detroit and I had to talk to all the various departments and it was in the sculpture department that they asked me what I thought about sculpture. Then these ideas came up and I spoke rather interestingly because of the situation and the questions that were asked. I insisted that sculpture should do something to respond to music. Also to the whole question of society and the environmental problems now. I find it horrifying that Buckminster Fuller [visionary, 1895-1983] can make it very clear that less is more and that there is an energy shortage and a metal shortage and that the sculptures can continue to use huge, heavy amounts of metal.

PC: They should try something else.

JC: I suggested that they make perishable sculptures that would be social events like compositions of music, and I pointed out that the moment happens in the city, being made like a building being constructed, that it excites, interests, and moves through the whole society, rather than just to the --

PC: How did they like that?

JC: I think they were stimulated. We went on and on thinking of possibilities. Also that relates to American Indians.

PC: How do you like lecturing to the universities? Because you seem to --

John Cage, David Tudor, Yoko Ono, and Mayuzumi Toshiro, Music Walk, 1962.

JC: I do, I do as little as possible.

PC: Because you've done a lot of it over the years.

JC: Yeah, an awful lot. I'm opposed to institutions and yet saying so I bite the mouth that feeds me. I could now live in some part of the earth, from my books and my music. So that I don't really need to be fed by those universities and I have for many years talked against them.

PC: The more you talk against them, the more they want you.

JC: Yeah.

PC: The more they want you. What did you do at Wesleyan? That institute for advanced --

JC: That never took place. I was the fellow in The Center for Advanced Studies and the fellow in The Center of Humanities, I think it was called. It was the same center, I just continued my work.

Marcel Duchamp. Secret Noise

PC: What was it like to work there?

JC: I gave a few talks but essentially I just was in the community. It was not teaching but just being there, for everyone. Except, perhaps Albers, I think he really taught.

PC: I think so.

[END OF INTERVIEW]

Alan Fletcher, John Cage (1993)

MORE in PREPARED GUITAR

1974 Interview with John Cage by Paul Cummings I/II

John Cage and David Tudor - Music in the Technological Age (September 15, 2015)John Cage and Morton Feldman In Conversation (September 8, 2015)

4'33'' Cage for guitar by Revoc (July 10, 2015)

John Cage: An Autobiographical Statement (May 22, 2015)

Angle(s) VI John Cage (April 30, 2015)

Morton Feldman (March 16, 2015)

Morton Feldman and painting (October 3, 2014)

Morton Feldman Page

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb()/discogs-images/R-4110980-1404360851-2206.jpeg.jpg)