Despite years of research, the details of William Lee Conley Broonzy's birth date remain problematic. He may have been born on 26 June 1893 - the date of birth he often gave - or according to Bill's twin sister Laney, it may have been in 1898. Laney claimed to havedocuments to prove that. However, definitive research undertaken by Bob Reisman (see www.amazon.co.uk or www.amazon.com search book "I Feel So Good") has changed the picture.

Bill often regaled audiences with tales of his birth on 26 June 1893 and that of his twin sister Laney and of his father's response to being told he had twins to care for. He claimed to have served in the US Army in France from 1918 - 1919 and to have been invited by a record company to travel to the Delta following a major flood in 1927: Turns out, that a good deal of this was fiction at worst and faction at best.

Robert Reisman's impeccable research suggests a birth date for Bill of 26th June 1903 (and in Jefferson County, Arkansas, not Scott Mississippi as previously suggested). Laney was not a twin at all but four years older than Bill. (She was born in 1898).

Bill spoke and sang about experiences in the US army and of his return from France to Arkansas/Mississippi. It turns out though, that the reported army experience was Bill's factional description of an amalgam of the stories told by black soldiers returning from overseas. A trip Bill claimed to have made to Mississippi in 1927 to the flooding was similarly untrue, but was a factional account into which Bill inserted himself.

Broonzy is/was not even his real name. He was born into the world with the name Lee Conly (note spelling) Bradley; and so it goes on.

Bill's father Frank Broonzy (Bradley) and his mother, Mittie Belcher had both been born into slavery and Bill was one of seventeen children. His first instrument was a violin which he learned to play with some tuition from his uncle, his mother's brother, Jerry Belcher. Bob Reisman suggests that there is little evidence that Jerry Belcher existed.

In Arkansas, the young Bill (Lee) worked as a violinist in local churches at the same time as working as a farm hand. He also worked as a country fiddler and local parties and picnics around Scott Mississippi. Between 1912 and 1917, Bill (Lee) worked as an itinerant preacher in and around Pine Bluff. It is not known why he changed his name.

Later, he worked in clubs around Little Rock. In about 1924, Big Bill moved to Chicago Illinois, where as a fiddle player he played occasional gigs with Papa Charlie Jackson. During this time he learned to play guitar and subsequently accompanied many blues singers, both in live performance and on record. Bill made his first recordings in 1927 (just named Big Bill) and the 1930 census records him as living in Chicago and (working as a labourer in a foundry) and his name was recorded as 'Willie Lee Broonsey' aged 28. He was living with his wife Annie (25) and his son Ellis (6).

Over the years, Big Bill became an accomplished performer in his own right. Through the 1930s he was a significant mover in founding the small group blues (singer, guitar, piano, bass drums) sound that typified Chicago bues.

On 23 December, 1938, Big Bill was one of the principal solo performers in the first "From Spirituals to Swing" concert held at the Carnegie Hall in New York City. In the programme for that performance, Broonzy was identified in the programme only as "Big Bill" (he did not become known as Big Bill Broonzy until much later in his career) and as Willie Broonzy. He was described as:

"...the best-selling blues singer on Vocalion's 'race' records, which is the musical trade designation for American Negro music that is so good that only the Negro people can be expected to buy it."

The programme recorded that the Carnegie Hall concert "will be his first appearance before a white audience".

Big Bill was a stand-in for Robert Johnson, who had been murdered in Mississippi in August that year. Hammond heard about Johnson's death just a week before the concert was due to take place. According to John Sebastian (1939) Big Bill bought a new pair of shoes and travelled to New York by bus for the concert. Where he travelled from is, however, left dangling. The inference of the text is that it was from Arkansas, but as noted above, by by late 1938 Bill was established as a session man and band leader, and as a solo performer in Chicago. Within weeks of the 1938 concert Bill was recording with small groups in a studio in the windy city.

In the 1938 programme, Big Bill performed (accompanied by boogie pianist Albert Ammons) "It Was Just a Dream" which had the audience rocking with laughter at the lines,

"Dreamed I was in the White House, sittin' in the president's chair.

I dreamed he's shaking my hand, said "Bill, I'm glad you're here".But that was just a dream. What a dream I had on my mind.And when I woke up, not a chair could I find"According to Harry "Sweets" Edison, a Trumpeter with the Count Basie Orchestra, also in the concert, Big Bill was so overwhelmed by the audience response that he failed to move back stage as the curtain came down and got caught in front of it. Later, according to Edison) perhaps not realising he had to do a number in the second half of the concert,he was found to have left the Carnegie Hall and caught a bus home.

Regardless of the truth of that story, when a second concert was organised in 1939, on Christmas Eve, Bill was there again. This time, again with Albert Ammons, he performed two numbers: Done Got Wise, and Louise, Louise.

Broonzy updated his act by adding traditional folk songs to his set, along the lines of what Josh White and Leadbelly had done in then-recent times. He took a tremendous amount of flak for doing so, as blues purists condemned Broonzy for turning his back on traditional blues style in order to concoct shows that were appealing to white tastes. But this misses the point of his whole life's work: Broonzy was always about popularizing blues, and he was the main pioneer in the entrepreneurial spirit as it applies to the field. His songwriting, producing, and work as a go-between with Lester Melrose is exactly the sort of thing that Willie Dixon would do with Chess in the '50s. This was the part of his career that Broonzy himself valued most highly, and his latter-day fame and popularity were a just reward for a life spent working so hard on behalf of his given discipline and fellow musicians. It would be a short reward, though; just about the time the autobiography he had written with Yannick Bruynoghe, Big Bill Blues, appeared in 1955, he learned he had throat cancer. Big Bill Broonzy died at age 65 in August, 1958, and left a recorded legacy which, in sheer size and depth, well exceeds that of any blues artist born on his side of the year 1900.

The situation back in America was more complex for Broonzy. In Chicago, young black people wanted to see the electric blues of rising stars such as Muddy Waters, and so Broonzy turned even more to acoustic ballads (although Waters himself remained a fan, recording a tribute album of Broonzy's songs and being a pallbearer at his funeral). Folk Bill became his own invention, critics said, but he became an inspirational figure for the (white) folk music revival movement. Some lovely footage from a summer camp, filmed by folk singer Pete Seeger on a 16 mm camera, shows Broonzy singing softly and smiling sweetly during a version of Worried Man Blues, even though, by this stage, he was very ill.

In 1940, Lester Melrose selected Bill to be one of the accompanists for his discovery Lil Green, who had crossed from being a blues singer to the status of pop star. "Romance In the Dark," a hit for Green that became a standard, was jointly credited to both Green and Broonzy. Broonzy's guitar playing features prominently in Green's 1941 rendition of Joe McCoy’s "Why Don't You Do Right?" a song that jumpstarted the career of Peggy Lee when she sang it with Benny Goodman's band. Broonzy accompanied Green on the first two of her cross-country tours; for her last two tours she opted to use a big band instead, but she and Broonzy remained friends.

Broonzy's guitar-accompanied vocal, "Key to the Highway," issued in 1941, was to be his most successful record. He had recorded this on Bluebird as guitar accompanist for his friend Jazz Gillum (vocal) in 1940. Another singer, Charles Segar, had cut a 12-bar version (with a slower tempo and different tune) some months before Gillum and Broonzy's eight-bar version. "Key to the Highway" is now usually credited to Broonzy and Segar. Broonzy's version would be covered by Brownie McGhee (1946), Little Walter (1958), John Lee Hooker (1959), Mance Lipscomb (1964), the Rolling Stones (1964), Eric Clapton (1970), Muddy Waters (1971), and Buddy Guy (1993), to name a few. In 2010, Broonzy's recording of "Key to the Highway" was inducted into the Blues Hall of Fame's Classics of Blues Recordings category.

In an interview with Studs Terkel, Broonzy explained how different performers can take the communal floating tunes and verses of a traditional song like "Key to the Highway" and make a it their own:

Broonzy: Some of the verses he [Charles Segar] was singing it in the South the same as I sang it in the South. And practically all of blues is just a little changed from the way that they was sung when I was a kid . . . . You take one song and make fifty out of it . . . just change it a little bit.

Terkel: This is your song, though. You wrote this oneBroonzy: Yeah I wrote it, yeah. In a way - I’ll say I wrote it, and Charles Segar [N-Dash]– he was in it too.Big Bill Broonzy Interviewed by Studs Terkel, Folkways LP FG 3586 (recorded 1956, issued 1960)

WWII brought a temporary interruption of commercial recording, as acetate was diverted to the war effort. When the industry resumed after the war it re-labeled race music as "rhythm-and-blues" and hillbilly/folk as "country music." As new labels entered the field, Bluebird began losing its preeminence. Public tastes were changing: black audiences began to prefer up-beat dance music like that of Kansas City's Big Joe Turner, with rocking rhythms and emphatic saxophone; or they danced to slow, crooned ballads.

Chicago's live music scene was also changing. The invention of mechanized cotton pickers had spurred a tremendous influx of hundreds of thousands of new migrants from the Mississippi Delta; sometimes called the "Second Great Migration," it eventually numbered five million. A rougher and more driving sound with electric guitar and wailing harmonica, now identified as "Chicago Blues," began to prevail in the clubs and on Maxwell Street. Established artists like Big Bill Broonzy, Big Maceo, and harmonicist Sonny Boy Williamson had paved the way for this. Broonzy and Memphis Minnie had been among the early adopters of the electric guitar in the early forties; Muddy Waters first heard the instrument from him, but Bill soon abandoned it, preferring the sound he had grown up with. Neither was he a fan of the new sophisticated "cool" bebop jazz that had developed stateside during the war. In his 1952 Paris interview with Alan Lomax, Broonzy complained about producers telling him he had to change his harmonies and the way he played: "These young boys playing this here bebop? They tells me the blues is old-fogey-ism (Land Where the Blues Began, 1995, p. 454), and in his autobiography, Big Bill Blues, Broonzy bemoans the fact that "some Negroes tell me that the old style of blues is carrying Negroes... back to slavery; and who wants to be reminded of slavery? And some say this ain't slavery [time] no more, so why don't you learn to play something else? ... I just tell them I can't play nothing else."

When Alan Lomax visited Broonzy in Chicago to interview him in 1946, Bill introduced him to fellow musicians harmonica player Sonny Boy Williamson and pianist Memphis Slim. Some time later that year, Bill mailed Alan a six-page manuscript answering some of Alan's questions about the blues and about his life. Bill's ambition to tell his story to a wider public possibly had its origins here. In July of that year, Broonzy traveled to New York to sing at a Hootenanny given by People's Songs in New York, where he introduced "Black, Brown, and White," to an enthusiastic audience of mostly white progressives and civil rights activists. Soon he was a performing regularly at the Chicago branch of People's Songs, appearing with Pete Seeger and Doc Reese, among others. On November 9, 1946, he returned to New York to perform with Sidney Bechet and Sonny Terry at Alan Lomax's Blues at Midnight, one of a series of bi-weekly Midnight Special concerts at Town Hall, also sponsored by People's Songs. This concert was so successful that in February 1947 Alan Lomax put on a second Town Hall Blues at Midnight concert, this time entitled Honky-Tonk Blues at Midnight, at which Broonzy, Memphis Slim, and Sonny Boy Williamson were featured performers.

The day after their Town Hall performance Alan brought the three musicians to the Decca studios to record them. They had all been staying in New York as guests at Alan Lomax's Greenwich Village apartment, where they had socialized with Alan's wife Elizabeth and baby daughter Anna, and the three felt quite comfortable in Lomax's presence. At Decca, Alan sat on the floor at the musicians' feet, changing the discs in the small portable recording machine, while Broonzy asked the other two about the origins of the blues. Perhaps forgetting at times that their words were being recorded, they began answering the question by explaining that most blues deal with the trials and tribulations of love. Soon, however, they all started talking frankly and openly among themselves about conditions for black people in the Jim Crow South, mentioning lynchings and other abuses - such as summary executions of black workers by levee work-crew bosses. They recalled how dangerous it was for a black man to be perceived as clever at figures, or to be seen reading newspapers such as the Chicago Defender, which used to be read aloud in secret. "They recalled the challenges of life in the Mississippi work camps where the penitentiary stood at the end of the road waiting to receive the rebellious. Then, overwhelmed by the absurdities of the Southern system they had described, they laughed their way to the end" (Alan Lomax, liner notes to Blues in the Mississippi Night.) It was a side of Southern life that was normally taboo for blacks to mention and that white people, especially white Southerners, resolutely closed their eyes to, in deference to the prevailing dogma that black people were contented with their lot.

They had put on record the unknown Southern story with all of its violence, tragedy, and absurdity, exposing things that Twain didn’t know and Faulkner didn’t tell us. To me it seemed that a new order of documentation had emerged, in which members of a tradition presented their own cases to each other [N-DASH]– unscripted, unprompted, and without an intermediary. But Big Bill and his friends had a different reaction. - Notes to Blues in the Mississippi Night

When Lomax played the recordings back to them, the men insisted that he not tell anyone they had made them. "You don't understand, Alan. If these records came out on us, they'd take it out on the folks down home - they'd burn them out and Lord knows what else." The realization that the terror that enforced the Southern system should reach as far a New York and Chicago was sobering and disturbing to Lomax. He honored their wishes, concealing their identities until all three men were dead. Later that year, however, with Broonzy's permission, he read excerpts from the interviews aloud at a meeting of the American Folklore Society (they were later included in Alan Dundes's anthology, Mother Wit from the Laughing Barrel: Readings in the Interpretation of Afro-American Folklore, University Press of Mississippi, 1973, 1990). Selections from the transcripts were printed in fictionalized form under the title "I Got the Blues" in the Summer 1948 (pp. 38-52) issue of Common Ground, an influential quarterly magazine dedicated to the promotion of cultural diversity, whose editorial board included Langston Hughes, Thomas Mann, and Lin Yutan.

With the rise of electric blues in the early 1950s, Broonzy became an active supporter of the folk blues genre. In 1951, Broonzy took his first tour of Europe, where he was met with enthusiasm and appreciation. His appearances in Europe introduced the blues to European audiences and were especially influential in London’s emerging skiffle and rock blues scene. Broonzy’s success also set the stage for later blues artists such as Sonny Boy Williamson II and Muddy Waters to play European venues. Broonzy toured Europe again in 1955 and 1957.

August 15, 1958, Big Bill Broonzy dies in Chicago from complications with cancer. Many blues men including Muddy Waters attend his funeral. In July 1957, a day before he had an operation for throat and lung cancer, the blues singer Big Bill Broonzy finished recording his final album. “Man, this is a helluva night, Is there gonna be any whiskey?” he said.

The Last Sessions, made for Verve Records in Chicago, captured his hauntingly sad voice in versions of blues classics such as Key to the Highway and the gospel Swing Low, Sweet Chariot.

One song Broonzy declined to sing was Black, Brown and White, his bold anti-racism song that Decca and RCA refused to issue in the Forties. “But as you’s black, oh brother, get back, get back, get back,” went the lyrics.

Bibliography

Broonzy, Bill, and Yannick Bruynoghe. Big Bill Blues. London: Cassell &Co., 1955.

Broonzy, Bill. The Bill Broonzy Story. CD box set. Polygram Records, 1999.

His Story: Big Bill Broonzy Interviewed by Studs Terkel. CD. Smithsonian Folkways, 2012.

House, Roger Randolph. “‘Key to the Highway’: William ‘Big Bill’ Broonzy and the Chicago Blues in the Era of the Great Migration.” PhD diss., Boston University, 1999.

Palmer, Robert. Deep Blues. New York: Penguin, 1981.

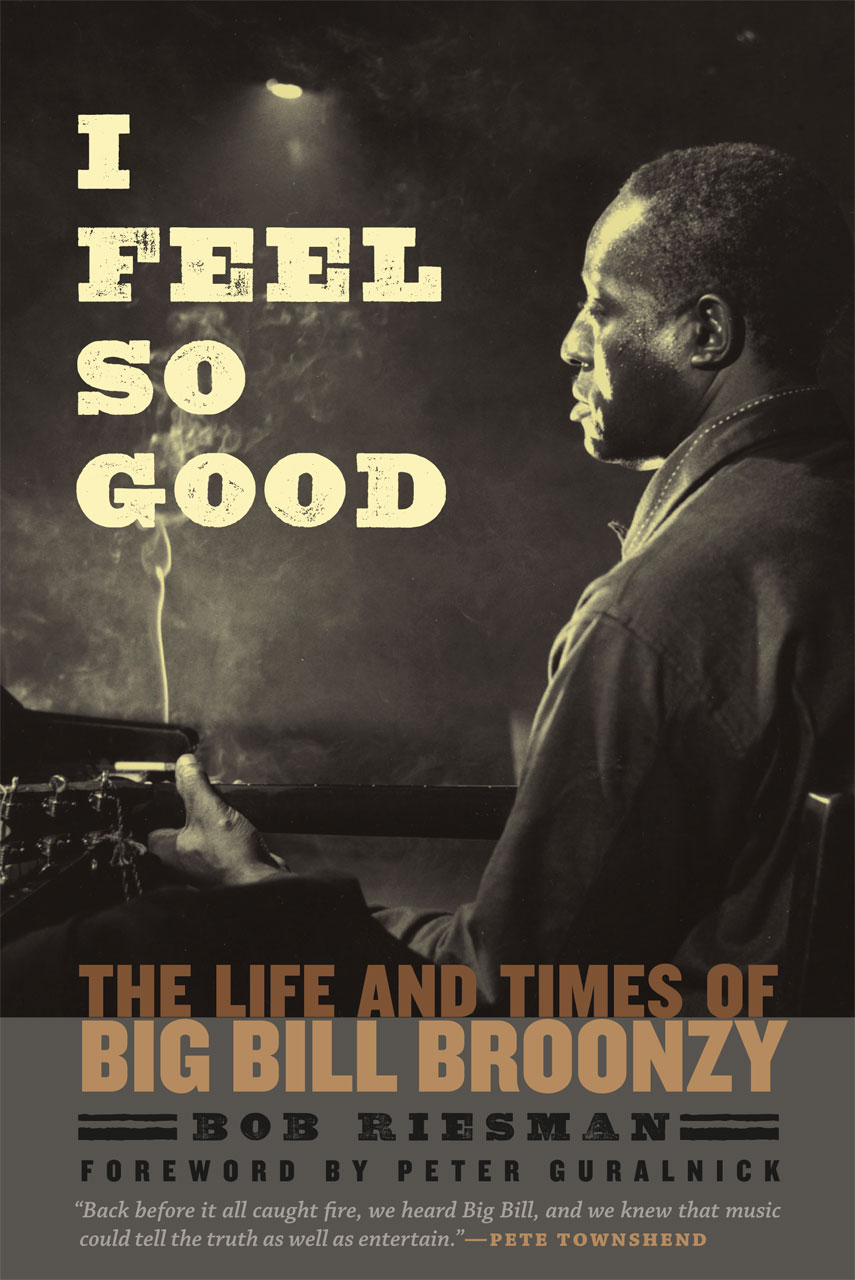

Riesman, Bob. I Feel So Good: The Life and Times of Big Bill Broonzy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011.

Sources

http://www.allmusic.com/artist/big-bill-broonzy-mn0000757873

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/tvandradio/10480580/Big-Bill-Broonzy-legacy-of-a-musical-pioneer.html

http://www.culturalequity.org/alanlomax/ce_alanlomax_profile_broonzy.php

http://blues.about.com/od/artistprofil2/p/Broonzyprof.htm

http://www.bbc.co.uk/music/artists/05bc49f8-3108-44c8-82b9-ac3254896a69

http://www.press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/I/bo6701925.html